In 2002, it was established that White’s Skink (Liopholis whitii) was three separate species – White’s Skink (Liopholis whitii), Guthega skink (Liopholis guthega) and Mountain Skink (Liopholis montana)

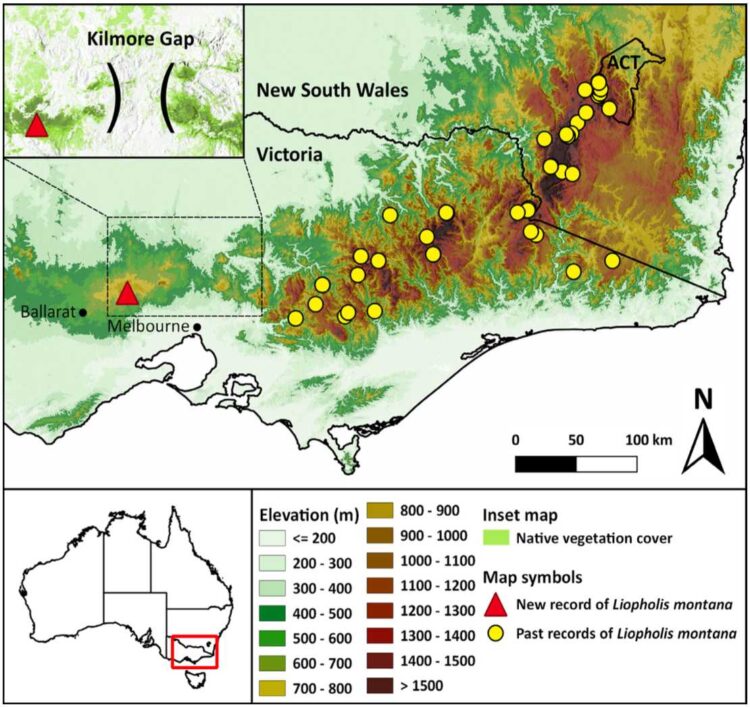

It was thought that the Mountain Skink only existed along the Great Divide between the ACT and Yea and at an elevation of between 900 and 1800 metres.

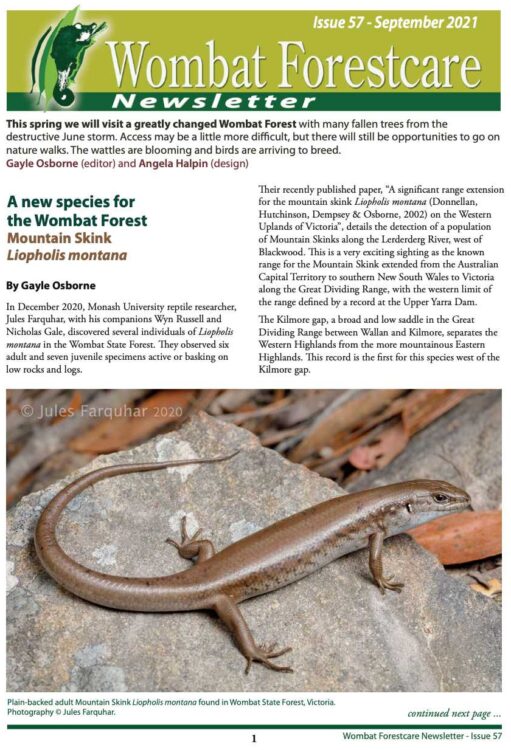

In 2020, while on a bush walk in the Wombat State Forest, ecologist Jules Farquhar and two colleagues observed a number of Mountain Skinks basking in the sun. The elevation of the location was 620 metres, far lower than elevations where they have previously found.

This was an incredibly exciting discovery and showed that we cannot assume that the Wombat Forest has been adequately surveyed for all its species.

In August 2022, Liopholis montanawas listed as Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Throughout its range it occurs in a series of apparently isolated subpopulations at elevations ranging from 620 m (Wombat State Forest) to 1800 m (Mt Gingera, ACT).

Wombat Forestcare became aware that leading reptile scientists Dr. Zak Atkins had genetic material (tail tips) from over 100 Mountain Skinks from across their range from the ACT to the Wombat Forest. This led to Wombat Forestcare raising the funds to perform DNA sequencing and have a specialist conservation geneticist, Dr. Michael Amor prepare a report. The report was titled “An assessment of population structure and genetic diversity of the mountain skink, Liopholis montana” and was authored by Drs. Michael Amor, Zak Atkins and Nick Clemann. DOWNLOAD REPORT

A further report “Isolation has led to reduced genetic diversity among populations of an endangered mountain specialist” authored by Drs. Michael Amor, Zak Atkins and Nick Clemann has been published Conservation Genetics. DOWNLOAD REPORT

The report established that

- The mountain skink had the poorest genetic diversity (i.e., the lowest fitness) among all studied high-elevation skinks in Australia

- The mountain skink occurs on four isolated peaks throughout southeast Australia, and these four populations required individual conservation; and

- The Wombat State Forest was the largest population and had the greatest genetic diversity, which highlighted its potential to act as a ‘genetic resource bank’ to benefit the conservation outcomes across the species’ range.

Elevation map showing sampling localities of the mountain skink, Liopholis montana, in Victoria, New South Wales, and the Australian Capital Territory, Australia (A). Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC) plot of 92 Liopholis montana individuals collected from 25 sites along the Great Dividing Range in southeastern Australia (B). Summary of 20 fastStructure runs for 92 Liopholis montana individuals (x-axis) collected from 25 sites in southeastern Australia (black vertical lines)

Mountain Skinks live in a system of burrows are believed to pair for life. The female gives birth to live young, with the juveniles sharing the burrows for some time before dispersing.

A pair of Mountain Skinks were observed mating in October 2024. Male skinks have a pair of hemipenes, which are intromittent organs that are used for reproduction. They are held within the body and are everted for reproduction.

-

Mountain Skinks copulating.

-

Male Mountain Skink after copulation.

-

The Mountain Skinks resting in the sun after copulation.

The genetic samples from Mountain Skinks for the reports were sourced from relatively close locations and since that time, Mountain Skink populations have been located in a far more extensive area, including in the Lerderderg State Park.

Dr Zak Atkins has now sourced over 140 genetic samples from 54 colonies in the Wombat State Forest and the Lerderderg State Park.

Wombat Forestcare is now raising funds for the genetic sequencing of these samples and a report to be written.

The aim is to

- quantify the genetic diversity of all 54 colonies found in the Wombat State Forest and Lerderderg State Park;

- provide a detailed account of how colony loss results in irreversible genetic diversity loss;

- highlight priority colonies and areas for conservation (those that contain a high level of unique genetic diversity); and

- provide evidence-based advice to land managers on burn exclusion areas to help safeguard the mountain skink and its habitat. Outcomes from this research will improve habitat protections within this area, which will benefit not only the mountain skink, but also many species that call the Wombat State Forest and Lerderderg home.

More Information

Read the scientific paper regarding the discovery of Mountain Skinks in the Wombat State Forest: A significant range extension for the mountain skink Liopholis montana (Donnellan, Hutchinson, Dempsey & Osborne, 2002) on the Western Uplands of Victoria

Download Clemann 2024 Mountain Skink Liopholis montana preventable threats exacerbate climate change